CME credit available from Harvard Medical School through September 2024.

Published Materials

The goal of this educational program is to provide primary care clinicians with a review of evidence-based practices for the evaluation and management of heart failure in primary care settings, including summaries of recent changes to HF treatment guidelines.

Despite recent incentives and improvements in care, heart failure continues to be a leading cause of hospitalization in the U.S.1,2 Ensuring patients are on guideline directed medical therapy is one way to reduce rehospitalization. Yet many patients are not on recommended therapy.3,4

Guideline recommended treatment depends on heart failure symptoms and ejection fraction (EF).

HF with reduced EF EF <40%

HF with preserved EF EF >50%

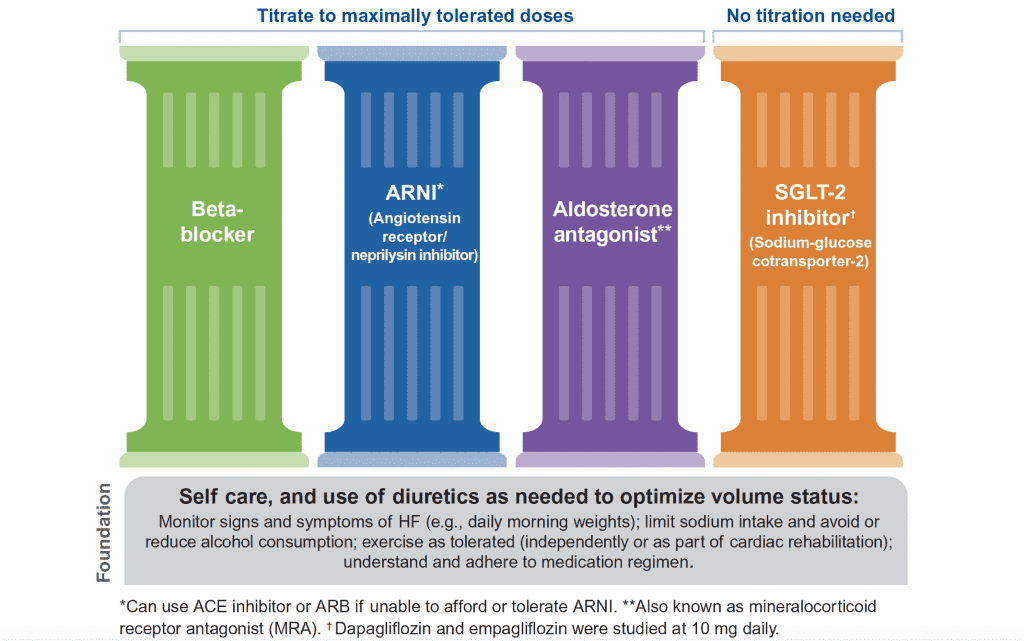

HF with reduced EF is best managed with four medications on a foundation of self-care and diuretics5

These medications have been shown to reduce HF hospitalization and death for people with HFrEF. Other options may be useful in specific patient cases: hydralazine/isosorbide, ivabradine, vericiguat, and digoxin.

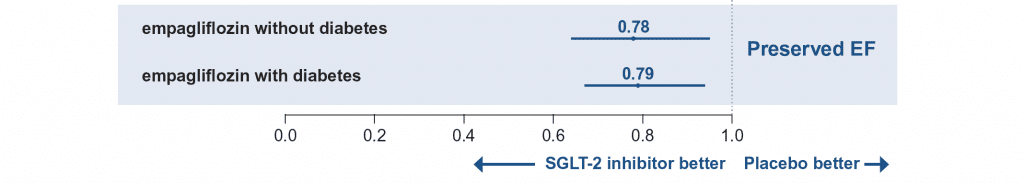

Patients with HFpEF do not have the same response to the four pillars. Recently, data on empagliflozin suggests a benefit in HF hospitalization and mortality for patients with HFpEF regardless of the diagnosis of diabetes.6

Empagliflozin has been shown to reduce HF hospitalizations and death in patients with preserved EF6

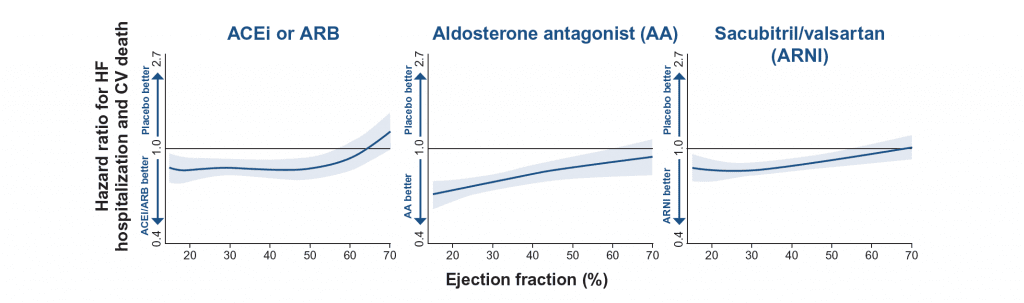

The trial for empagliflozin is groundbreaking because previous trials of medications in HFpEF have not shown clear benefit. Analysis of these prior trials suggests that benefit seen may vary based on the EF.

Additional medication options for patients with an EF >40% depends on the patient’s EF.

For patients who have advancing or advanced heart failure, discussions about goals of care and treatment options available become critical. One registry of patients with heart failure found patients with advanced heart failure are not always prepared to make end-of-life decisions, with more than 1 in 3 not having either a health care proxy or advance care directive in place.7

Information current at time of publication, September 2021.

The content of this website is educational in nature and includes general recommendations only; specific clinical decisions should only be made by a treating clincian based on the individual patient’s clinical condition.

References

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Fast Facts. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/faststats/NationalDiagnosesServlet. Published April 2021. Accessed June 3, 2021.

- Virani SS, Alonso A, Aparicio HJ, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2021 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;143(8):e254-e743.

- Greene SJ, Fonarow GC, DeVore AD, et al. Titration of Medical Therapy for Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(19):2365-2383.

- Wirtz HS, Sheer R, Honarpour N, et al. Real-World Analysis of Guideline-Based Therapy After Hospitalization for Heart Failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(16):e015042.

- Maddox TM, Januzzi JL, Jr., Allen LA, et al. 2021 Update to the 2017 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway for Optimization of Heart Failure Treatment: Answers to 10 Pivotal Issues About Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(6):772-810.

- Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, et al. Empagliflozin in Heart Failure with a Preserved Ejection Fraction. New England Journal of Medicine. 2021.

- Warraich HJ, Xu H, DeVore AD, et al. Trends in Hospice Discharge and Relative Outcomes Among Medicare Patients in the Get With The Guidelines-Heart Failure Registry. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(10):917-926.