Published Materials

- Summary Brochure

- Evidence Document

- Reference Card

- Sleep Hygiene Sheet

- CBT-I Sheet

- Benzodiazepine Sheet

- Patient Brochure

The goal of this educational program is to provide primary care clinicians with the current evidence regarding the treatment of insomnia in older adults, focusing on the role of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), limitations of medications, and strategies for reducing use of benzodiazepines for insomnia.

As many as 1 in 3 Americans report difficulty sleeping, with more than 10% reporting daytime consequences like fatigue.1 Insomnia in the long term can impact other health conditions such as anxiety, major depression, chronic pain, diabetes, dementia, and cardiovascular disease.2

Primary care clinicians can help patients get better sleep. Patients should be asked about their sleep. In patients reporting sleep difficulties, reviewing symptoms of other co-occuring conditions (e.g., nocturia in heart failure, pain, or anxiety), adjusting timing of medications such as evening diuretics, or identifying other sleep disorders (e.g., obstructive sleep apnea) are medical options to improve sleep. If further discussion is required, patients should be asked about the nature of the sleep difficulty, frequency, duration, and about current sleep habits. Opportunities to improve current sleep habits should include a discussion of good sleep hygiene.

Healthy behaviors can improve sleep

The best intervention for insomnia is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I)

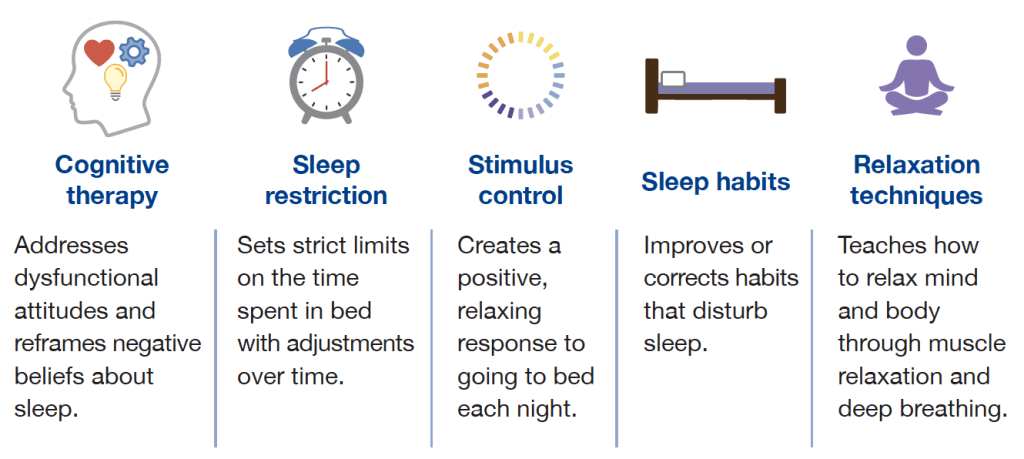

It is a series of behavioral interventions that targets the root causes of sleep problems by addressing sleep-related thoughts, emotions, and behaviors.3 CBT-I is a time limited intervention, consisting of 4-8 hours of training over several weeks to learn and implement the strategies of CBT-I.

The central elements of CBT-I

The components of CBT-I are most effective in combination. A comprehensive CBT-I program works better than the individual components on their own.4

It is effective when delivered in a variety of formats.5 Help patients pick the one that is best or most accessible for them.

Medications for insomnia

Several classes of medications have been found effective for the treatment of insomnia.6 These include:

- dual orexin receptor antagonists (DORAs)

- melatonin receptor agonists

- sedating antidepressants (e.g., doxepin)

- benzodiazepine receptor agonists, also called Z-drugs (e.g., zolpidem, eszopiclone, zaleplon)

- benzodiazepines

Principles for deciding which medication to use in older adults

- Match the treatment with the sleep concern (e.g., sleep latency, waking after sleep onset, or both)

- Select a medication with a better safety profile.

- Low-dose doxepin (1-6 mg), ramelteon, and DORAs have the least concerning side effects in older adults.

- Benzodiazepines and Z-drugs are not recommended for older adults.7

- Use caution with over the counter medications.

Reduce benzodiazepine and z-drug use for insomnia in older adults

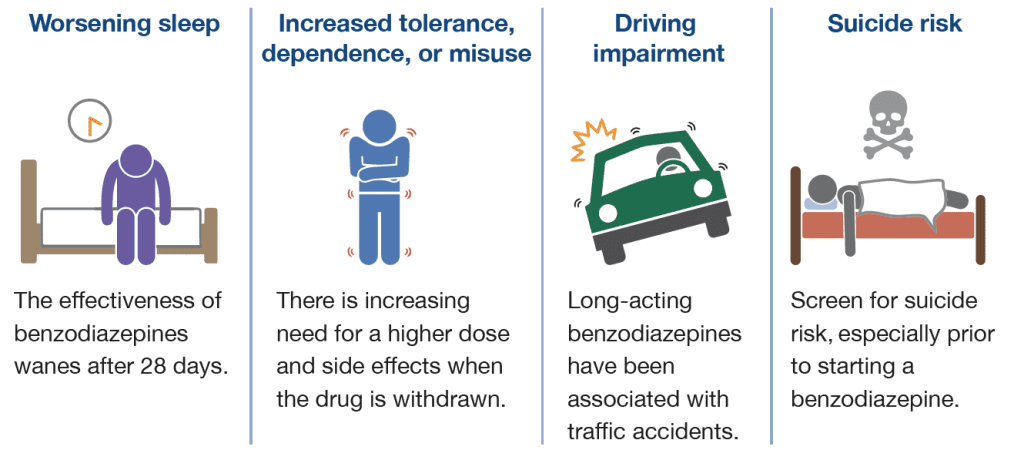

While these medications may be useful in the short term, long term use can result in risky side effects.

Risks from long-term benzodiazepine use include:

Patients who have these and other significant risks should reduce to a lower benzodiazepine dose or stop use with a taper. Several taper strategies have been studied such as a fast taper (i.e., a 25% dose reduction every 1-2 weeks), a symptom guided taper, or a partial dose taper (e.g., reduce by a set amount – half a tablet – each week).

Z-drug risks include cognitive impairment, falls or fractures, next day somnolence, and sleep-related behavior disturbances (e.g., sleep-eating, sleep-walking). For patients using higher than usual doses or long term continuous use, a dose reduction strategy may be needed to help patients stop use or switch to another, safer medication.

Patient resources

- In-person CBT-I

- Telehealth platforms

- Digital Apps

- CBT-I Coach

- the sleep reset (Apple or Google Play)

- sleepio (Apple or Google Play)

- night owl

- Online CBT-I modules

- AASM Healthy Sleep Habits

Information current at time of publication, March 2024.

The content of this website is educational in nature and includes general recommendations only; specific clinical decisions should only be made by a treating clinician based on the individual patient’s clinical condition.

References

-

Morin CM, Jarrin DC. Epidemiology of Insomnia: Prevalence, Course, Risk Factors, and Public Health Burden. Sleep Med Clin. 2022;17(2):173-191.

-

Perlis ML, et al. Why Treat Insomnia? J Prim Care Community Health. 2021;12:21501327211014084.

-

Edinger JD, et al. Behavioral and psychological treatments for chronic insomnia disorder in adults: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17(2):255-262.

-

Furukawa Y, et al. Components and Delivery Formats of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Chronic Insomnia in Adults: A Systematic Review and Component Network Meta-Analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2024 Jan 17:e235060.

-

Benz F, et al. The efficacy of cognitive and behavior therapies for insomnia on daytime symptoms: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2020;80:101873

-

Sateia MJ, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Pharmacologic Treatment of Chronic Insomnia in Adults: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017 Feb 15;13(2):307-349.

- American Geriatrics Society 2023 updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71(7):2052-2081.