Evidence-based Clinical Guidelines for Acute Pain

Published Materials

Acute pain is a frequent problem and its prevalence has been shown to increase with age. Effective treatment of acute pain is reduces suffering, improves return to function, and importantly, may help prevent progression to chronic pain. In particular, early intervention among those with acute pain leads to reduced persistent pain and better long-term function. This module discusses the evidence-based management options, both drug and non-drug, for addressing acute pain.

Managing acute pain

It is important to find the right balance between under-treating acute pain and over-medicating for a self-limited condition. In many cases, the cause of a patient’s pain is benign, and the most effective treatment may be to reassure patients that the underlying condition will usually improve on its own with time. However, in some cases, clinicians may not do enough to treat pain, missing an opportunity to reduce suffering and speed functional recovery.

The goal of optimal pain treatment is not to eliminate pain, but rather to relieve suffering and improve function while minimizing the harms and risks associated with treatment.

Selecting a pain regimen

Several medication choices can relieve acute pain without needing to resort to addictive drugs. A commonly used non-drug intervention for acute musculoskeletal pain is rest, ice, compression, elevation (RICE). Common first-line drugs for mild to moderate pain include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), acetaminophen, or topical agents. The choice between the types of medications may be driven by patient comorbidities or concerns about drug-related adverse effects.

If opioids are needed for acute pain

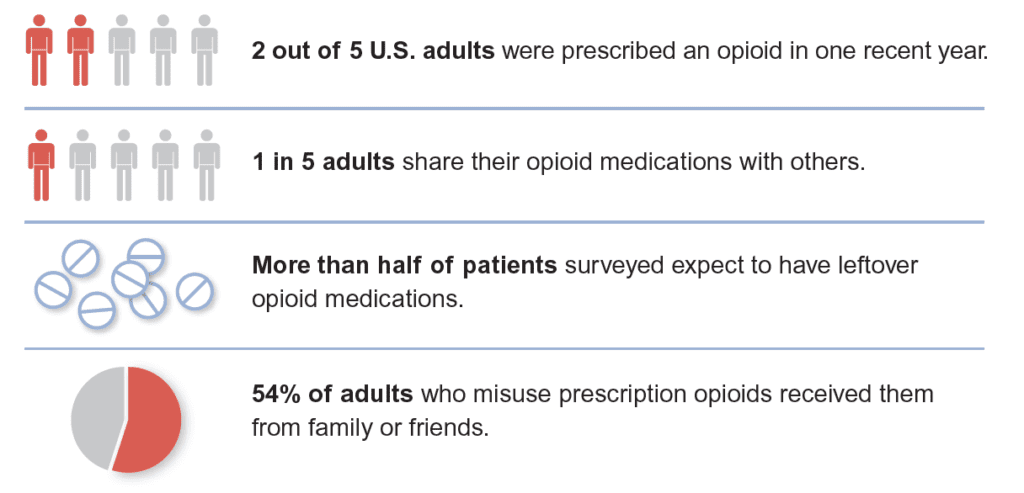

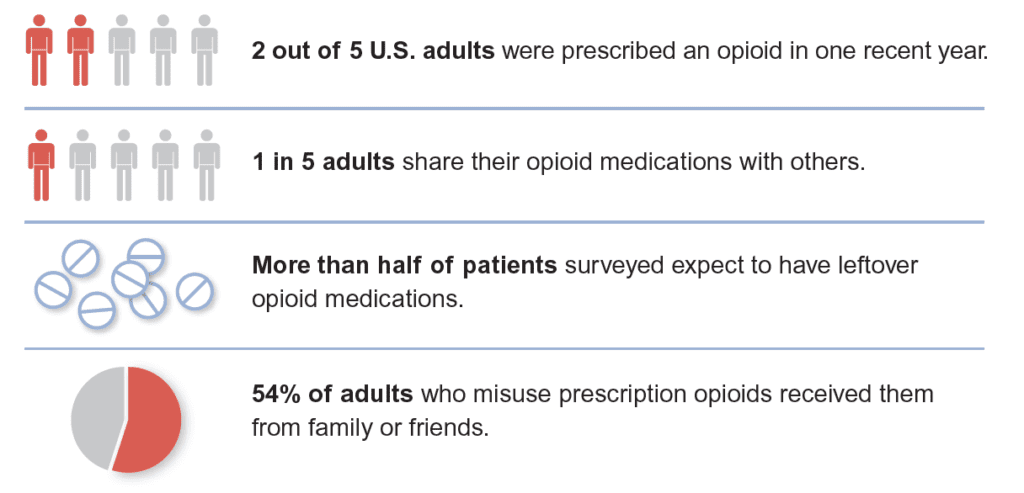

Opioids should only be utilized for acute, non-cancer pain after inadequate response to non-opioid therapies. These drugs should be used cautiously because of the risk of addiction and overdose, even with short-term use. In many cases, the risk of addiction and overdose may be due to access to unused prescription opioids.

Leftover prescribed opioids increase the risk of addiction, accidental overdose, and diversion.

Therefore, when opioids must be used for acute pain, follow these principles:

- Prescribe short courses, usually less than three days.

- Continue non-opioid treatment, such as non-drug approaches, NSAIDs, and/or acetaminophen.

- Avoid co-prescribing with benzodiazepines, as this can increase the risk of overdose death by over two-fold.

- Avoid long-acting or extended release (ER) opioids.

- Counsel patients on safe storage and disposal.

Information current at time of publication, August 2019.

The content of this website is educational in nature and includes general recommendations only; specific clinical decisions should only be made by a treating physician based on the individual patient’s clinical condition.

References

- Fries BE, Simon SE, Morris JN, Flodstrom C, Bookstein FL. Pain in U.S. nursing homes: validating a pain scale for the minimum data set. Gerontologist. 2001 Apr;41(2):173-9.

- Morrison RS, Flanagan S, Fischberg D, Cintron A, Siu AL. A novel interdisciplinary analgesic program reduces pain and improves function in older adults after orthopedic surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009; 57:1–10.

- Wong-Baker FACES Foundation (2018). Wong-Baker FACES® Pain Rating Scale. Retrieved [Date] with permission fromhttp://www.WongBakerFACES.org.

- Brat GA et al. Postsurgical prescriptions for opioid naive patients and association with overdose and misuse: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2018 Jan 17;360:j5790

- Sun EC et al. Association between concurrent use of prescription opioids and benzodiazepines and overdose: retrospective analysis. BMJ. 2017 Mar 14; 356:j760.