CME credit available from Harvard Medical School through January 2026.

Published Materials

- Summary Brochure

- Evidence Document

- Reference Card

- Patient Brochure

- Resource Tear Off

- PHQ Tear Off

- Safety Plan

The goal of this activity is to educate prescribers about the most recent evidence relating to defining and diagnosing depression in older adults, as well as different treatments used to manage the condition.

Depression is not a normal part of aging. It is a cluster of symptoms that causes functional impairment lasting longer than two weeks with medical, functional, and social consequences. Yet depression is under-treated, with fewer than 3 in 10 patients with a positive depression receiving any treatment.1 80% of depression treatment for older adults is provided by primary care clinicians.2

Take steps to identify patients with depression

- Screen all patients using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) – 2

- Identify whether major depressive order is present with the PHQ-9 or Geriatric Depression Scale

- Use the score to identify recommended treatment

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapeutic approaches like cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), behavioral therapy, or interpersonal therapy are as effective as medications for the management of depression.3

Encouraging patients to engage in activities they enjoy can help.

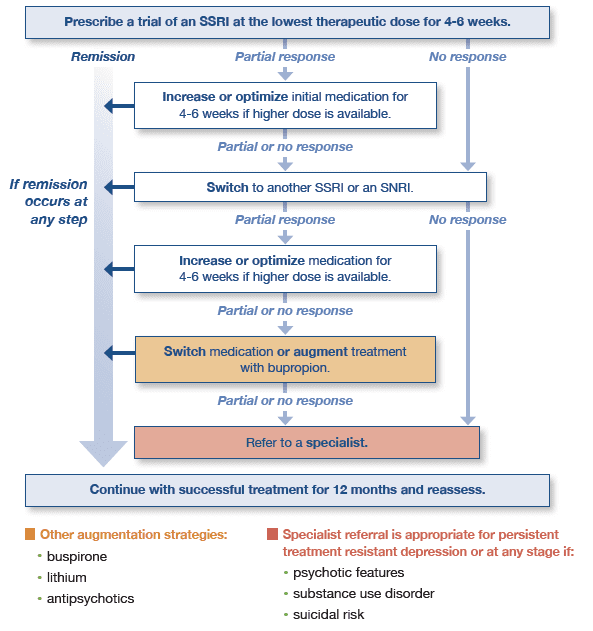

Medications

Selective serotonin receptor inhibitors (SSRIs) remain the first-line treatment for depression.

A framework for managing medication therapy

See the summary brochure above for more detailed information about dosing.

Older adults have the highest rates of suicide in the U.S.4 The SAFE-T framework can help create a plan to keep patients safe by providing a plan and linking with treatment.5

Provider resources

Patient resources

Information current at time of publication, January 2023.

The content of this website is educational in nature and includes general recommendations only; specific clinical decisions should only be made by a treating clinician based on the individual patient’s clinical condition.

References

-

Olfson M, et al. Treatment of Adult Depression in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(10):1482-1491.

-

Kessler RC, et al. Age differences in major depression: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Psychol Med. 2010;40(2):225-237.

-

Cuijpers P, et al. Psychotherapies for depression: a network meta-analysis covering efficacy, acceptability and long-term outcomes of all main treatment types. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(2):283-293.

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Disparities in suicide. 2022; https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/facts/disparities-in-suicide.html. Accessed Dec 22, 2022.

-

Suicide Prevention Resource Center. Suicide assessment five-step evaluation and triage SAFE-T pocket card. https://www.sprc.org/resources-programs/suicide-assessment-five-step-evaluation-and-triage-safe-t-pocket-card. Accessed Jan 3, 2023.